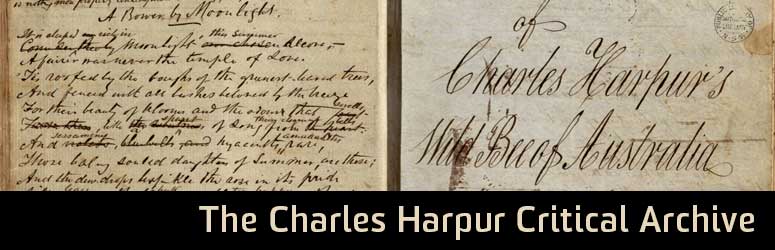

The Charles Harpur Critical Archive

Overview until 2013

This ARC-funded project began in late 2009. Still in development, it may be found at charles-harpur.org It was consciously designed as a digital publication from the start. CIs are Paul Eggert and Elizabeth Webby, with PI Peter Robinson of the University of Saskatchewan. The AustESE editorial tools and workflow development project, described elsewhere on the ASEC website, is also providing a publishing system during the development phase. The project's archive will ultimately be preserved at the University of Sydney library and published in collaboration with Sydney University Press and online.

Background: Harpur as colonial poet of a nation

In his high ambition to become known as the singer of a nation in the making, New South Wales colonial poet Charles Harpur (1813–68) would be unsuccessful, at least as judged by the appearance of his works in conventional book form. He signed one of his manuscript volumes with great resonance: ‘Charles Harpur/ An Australian’. In fact, no-one in the Australasian colonies was successful in carving out a literary career until near the end of the nineteenth century, and even then it was exceedingly rare; so Harpur’s failure is unsurprising. His reception in the colonial print culture in fact lay elsewhere.

Born in 1813 to a schoolmaster father, Harpur started publishing in newspapers and short-lived magazines in the early 1830s while New South Wales was still a penal colony and when the reading public there was tiny. Harpur harboured Wordsworthian ambitions to turn the Australian forest and bushland into the stuff of poetry. He was the first writer to attempt to deal seriously with local realities, producing tragedies and epics on colonial subjects at a time when it was generally assumed that Australian material was unsuitable for work in the higher literary genres. Yet he was also one of the most accomplished of those writing comic and satirical poems on political and other local events.

The proposals to revive transportation, the contentious land regulations, the question of what future or flowering the infant colony might achieve and the republican question during the 1840s and 1850s define the wider historical terrain that his poetry extensively traversed. For Harpur, it meant addressing, in addition, broader questions of ethics, aesthetics and political philosophy.

His often evolving prose notes to his poems are significant here. Over the years, Harpur republished some of his newspaper poems in other newspapers, often adding notes to each new printing, or revising the existing ones. The notes are occasionally more interesting than the poems themselves. They constituted an attempt on his part to key the poems into the changing political and cultural agendas of the day.

Understanding Harpur's works: the problem of versions

In contrast to Harpur’s sometimes savage satires are his love poems, especially the series of sonnets initially addressed to ‘Rosa’, in reality Mary Doyle, whom Harpur courted from 1843 until her family eventually agreed to their marriage in 1850. She would ultimately arrange for the book publication of a selection of his poems, some fifteen years after his death.

It has not so far been possible to fully capture and therefore to rightly appreciate Harpur’s prolific interventions as a newspaper poet–commentator on the political, moral and social issues of colonial Australia. The present project aims to set that situation to rights.

As a developing text Harpur’s remarkable poem about the murder of whites by Aborigines, ‘The Creek of the Four Graves’, provides a case study of the editorial problem. The poem went through a number of versions from 1845 when it began as a poem of 209 lines, published in three parts in the Sydney Weekly Register. After several rewritings it grew into a poem of 410 lines the year before his death in 1868. The poem received its first book publication in 1883, shortened to 273 lines by a well-meaning literary friend whom Mary Harpur engaged to bring her mid-century poet-husband’s works, with their vocabulary now deemed old-fashioned, up to date.

Progress

So far it has proved possible to locate and transcribe 788 newspaper publications by Harpur. Behind those print publications lay a gradually evolving archive of manuscript versions. Over 2,700 of them are extant in notebooks, nearly all in Harpur’s own hand and now in the Mitchell Library in Sydney. He copied the contents of these notebooks over time from newspapers and from one another, but usually with alterations and revisions, and with re-sequencing of the contents – which is a significant factor in the interpretation of poetry collections. New poems were usually added and some deleted thus creating new manuscript collections, one by one. This process seems, for Harpur, to have stood in for the elusive book collection of his poems that he was always seeking but never achieved in his lifetime.

Rather than make good his thwarted ambition to the exclusion of his decades of creativity, the project aims to capture the significant stages of development of each poem, version by version, to record their changes, annotate the elusive wordings with textual, historical and other commentary and to open up the whole unfolding archive for interpretation of all kinds by collaborating scholars. Images of virtually all of the versions have been obtained and organised alongside the transcriptions. To view the latest version of this developing project see charles-harpur.org.